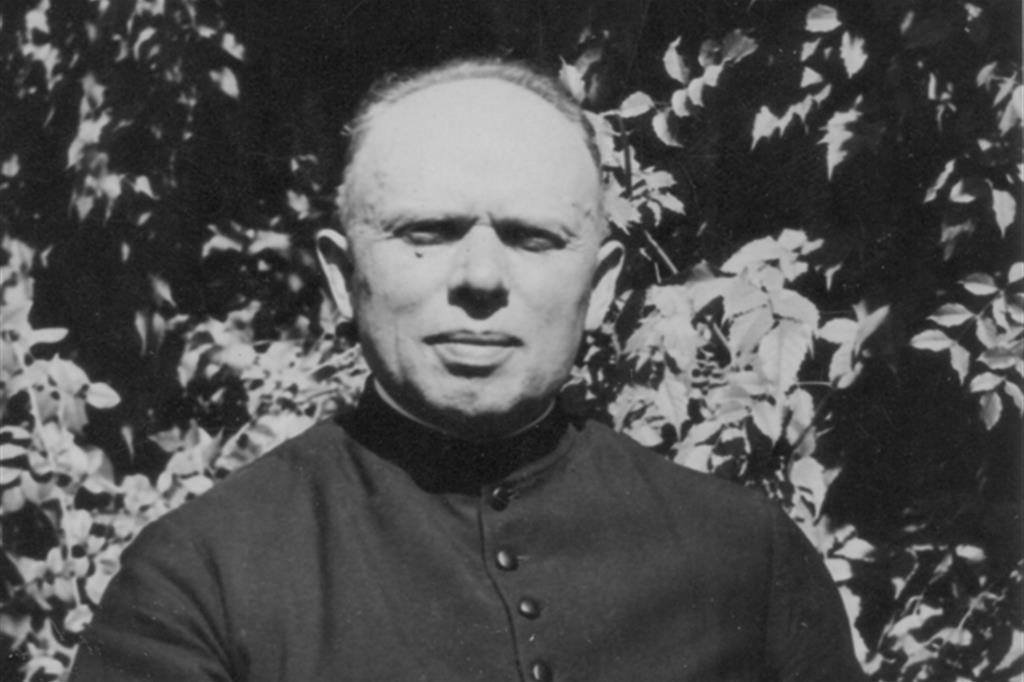

Cremona 13 January 1890 – Cremona 12 April 1959

Peasant Origins

Primo Mazzolari, the son of Luigi and Grazia Bolli, was born on January 13, 1890 in Boschetto, a small village in the province of Cremona in Northern Italy. His father supported the family as a small tenant fieldworker. Primo, the firstborn, was followed by Colombina, Giuseppe (Peppino), Pierina, and Giuseppina.

In 1900 the Mazzolari family moved to Verolanuova, in the province and diocese of Brescia, in order to find better work and living conditions. After completing elementary school two years later, Primo decided to enter the seminary. He attended the seminary in Cremona, where Bishop Geremia Bonomelli was celebrated for his Catholic-liberal ideas that conciliated with the young Italian State.

Life in the Seminary

Primo Mazzolari attended the Cremonese institute until 1912, when he was ordained priest. For the occasion, he returned to his family in Verolanuova, where he received the holy orders in the parish church from the Bishop of Brescia, Monsignor Gaggia. The following decade in Cremona proved very difficult for the young seminarian. These were severely repressive years of anti-modernism, launched by Pius X.

This situation resulted in more rigid discipline in the seminaries, the dismissal of professors deemed too innovative, and the end of any dialogue with contemporary culture. Mazzolari had to confront a series of vocational crises that he overcame with the enlightened help of the Barnabite priest, Pietro Gazzola, who had previously left Milan precisely because he was suspected of indulgence toward modernism. Father Gazzola predicted to the young Mazzolari that his adult life would be “a cross to bear.”

First Appointments

Once a priest, don Primo appointed vicar in Spinadesco (Cremona). The following year he transferred to his childhood parish church, Santa Maria del Boschetto. Soon after, in the fall of 1913, he was selected as a humanities teacher in the seminary grammar school. He assumed this role for two years and spent summer vacations with Italian emigrant workers in Arbond, Switzerland as a chaplan for the Bonomelli missions, similar in spirit and purpose to the more famous missions and religious order establishd by Bishop Scalabrini of Piacenza (a neighboring diocese).

Meanwhile, the First World War broke out and in the spring of 1915, vehement conflicts arose regarding Italy’s position in the war. don Mazzolari sympathized with the predicament of the democratic interventionists, as did other young Catholics, such as Eligio Cacciaguerra, the organizer of the Democratic Christian League and of the Azione newspaper from Cesena, to which Mazzolari contributed various articles. Primo decided to support Italian military intervention in order to eliminate the kind of militarism that was symbolized by Germany, to help establish a new democratic regime, and to facilitate international collaboration throughout Europe.

The Trials of War

The war immediately caused the young priest deep grief. In fact, his beloved brother, Peppino, who was killed in the battle of Sabotino in November 1915, always remained vivid in don Primo’s memory. He had, in any case, already decided to volunteer. He entered the Medical Corps and worked at hospitals in Genoa and then in Cremona. Concerned about feeling like a draft-dodger, don Mazzolari asked to be transferred to the front. In 1918, he became a military chaplain and followed the Italian troops to the French front. He remained in France for nine months. In 1919 he returned to Italy where he carried out other assignments for the Royal Army, including recovering the corpses of fallen soldiers along the North East front line. In 1920 he spent six months in Upper Slesia with Italian troops that were sent to maintain order in this region that, had been forced to cede from Germany and became part of the newly reconstructed Poland. All testimonial accounts point to the commitment and human passion with which don Primo supported the soldiers during this difficult time.

The Cicognara Period

After being discharged in August 1920, don Mazzolari asked his bishop, Monsignor Giovanni Cazzani, if, instead of teaching in the seminary, he could be assigned to pastoral work among the people. From October 1920 to December 1921, he was pastor of the parish church of the Most Holy Trinity in Bozzolo, a town in the province of Mantova, yet dependent on the diocese of Cremona. From here he was transferred as a pastor in the village of Cicognara, a short distance from the Po River, where he lived for a decade, until July 1932.

In Cicognara, don Primo gained experience as a parish priest, experimented with initiatives, reflecting upon and interpreted ideas, and—above all—searched for new ways to attract those who had turned away from the Church. The town, in fact, had a strong socialist undercurrent. In various ways, don Mazzolari appreciated popular peasant traditions, such as the grain and grape harvest festivals.

He also commemorated those killed in the war, engaged in patriotic celebrations, created a parish library and, held a night school for peasants in winter. He distrusted and was troubled by Fascism since its onset, and did not hide his intense opposition. Already in 1922, he wrote about those Catholics who were sympathetic toward the growing regime, “As paganism returns and brushes against us, few feel embarrassed.”

In November 1923 he refused to sing solemnly the Te Deum after an attempt on Mussolini’s life was thwarted. In 1929, in contrast to many enthusiastic bishops and priests, he did not vote in the plebiscite that Mussolini ordered after the signing of the Lateran Pacts, the international treaty that put an end to the opposition of the Vatican to the unification of Italy and granted political rights and privileges to the Church. Meanwhile, he refused any non-discerning exaltation of the war and militarism, and rejected all sectarian or partisan sentiments.

Even though he avoided openly taking a position of opposition, don Primo was soon considered an enemy in the eyes of the Fascists and an obstacle to the Fascist efforts in Cicognara. On the night of August 1, 1931 he was called to his window and shot at three times by a pistol. But fortunately, the bullets did not hit him.

A “Promotion” to Bozzolo

In 1932 don Primo was transferred to Bozzolo where two existing parishes had to be unified. For the occasion, he wrote a brief pamphlet, Il mio parroco (My Pastor), to greet the old and new parishioners. In fact, don Mazzolari began writing regularly in Bozzolo, making the thirties a prolific period of written works. In his books, he tended to present an idea of the Church beyond that of a “perfect society” by candidly confronting the weaknesses, negligence, and limits within the Church itself. In his opinion, this was necessary in order to finally present an evangelical message to the “lontani,” litterally the “far ones”, those who distanced themselves from the Church and renounced their faith precisely on account of sins committed by Christians and the Church. In his written works, don Mazzolari also declared that Italian society should be completely rebuilt, morally and culturally, and place more emphasis on justice, solidarity with the poor, and brotherhood. Such pronouncements inevitably forced him to deal with ecclesiastic as well as fascist censorship.In 1934 don Mazzolari published La più bella avventura (The Most Beautiful Adventure), based on the parable of the prodigal son. One year later, the text was condemned by the Vatican’s Holy Office (Sant’Uffizio), which declaired the book “erroneous” and demanded that it be taken out of commerce. don Mazzolari was obedient and gave in.

The Holy Office never explained to the poor priest which pages of the book were judged erroneous; perhaps they only took action on account of denouncements by some individuals in Cremona who were scandalized by the fact that local Protestants praised Mazzolari’s writings.Nevertheless, don Primo was not discouraged. In 1938 other texts by him appeared, such as Il samaritano (The Samaritan), I lontani (The Far Ones), and Tra l’argine e il bosco (Between the Dam and the Wood). This last text is a collection of various articles and writings in which don Mazzolari not only reveals his ideas about the parish church, but also his ability to observe nature and the reality of rural life. In 1939, he published The Way of the Cross of the Poor (La via crucis del povero).His successive works, however, ended up in the hands of the censors. In fact, in 1941 the fascist authorities censored Tempo di credere (Time to Believe) because it did not comply with the “spirit of the times,” that is, the spirit of Italy at war. Nevertheless, don Primo’s friends were able to secretly circulate a copy. In 1943 the Vatican’s Holy Office voiced its opinion again by condemning Impegno con Cristo (Commitment with Christ)—supposedly on account of the style utilized by the author.

The Period of Adesso

Many hopes for change were soon met with disappointment. don Mazzolari realized that he must create a more far-reaching movement. So, he dedicated himself in body and spirit to wage this battle with a newspaper. The first issue of the fortnightly Adesso (Now) appeared on January 15, 1949 during the height of the period when Catholic appeals against the Christan Democrats multiplied. (The following year, 1950, Giorgio La Pira published L’attesa della povera gente, The Poor are Waiting.)Within its pages, the newspaper wanted to touch upon all themes dear to its founder: an appeal for the renewal of the Church, the defense of the poor and the condemnation of social injustice, a dialogue with the people who left the Church, the problem of communism, and the promotion of peace during the cold war. Many collaborated to the newspaper, from don Lorenzo Bedeschi to Fr. Aldo Bergamaschi to the socialist Mayor of Milan, Anotnio Greppi, to many priests and lay catholics, more or less known, such as Franco Berstein, Father Umberto Vivarelli, Fr. Nazareno Fabbretti, Giulio Vaggi, and later, Mario V. Rossi.In the meantime, don Primo developed close relationships with the most free, open and critical voices within Italian Catholicism, which was then dominated by conformism and rigidity toward the contemporary world. Hence, he was friends with the founder of Nomadelfia, don Zeno Saltini, the poet Fr. David Maria Turoldo, the Florentine Mayor Giorgio La Pira, the writer Luigi Santucci, and many others.

The innovative and courageous character of Adesso once again provoked intervention from the Vatican to the extent that publication of the newspaper was ceased in February 1951. In July other personal measures against don Mazzolari were taken (prohibition from preaching outside of the diocese without approval from the bishops involved, and prohibition from publishing articles without pre-emptive ecclesiastical revisions). In November 1951, the newspaper was allowed to resume publication, but under the direction of a lay person, Giulio Vaggi. Don Primo collaborated, but under pseudonyms like Stefano Bolli. Some of “don Bolli’s” contributions about peace provoked further disciplinary actions. In fact, in 1950 the publication sparked an extensive debate about the (predominantly communist) Partisan Peace Movement’s proposal to ban the atomic bomb. Don Mazzoalri (who had also accepted Italy’s joining of the Atlantic Pact) declared that he was open to dialogue. All in all, the newspaper continued to live dangerously. Again, in 1954, don Primo received orders from Rome that he could only preach in his own parish and that he was forbidden from writing articles on “social matters.”

The Final Years

Using, as always, his characteristic discourse that aimed directly at provoking heart-felt emotions without indulging in scientific or sociological analysis, don Mazzolari published other significant works in the fifties.In 1952 La pieve sull’argine (The Parish on the Dam), an in-depth and highly autobiographical story, that retraced the events and vicissitudes of a country priest (don Stefano) during the last years of Fascism.The anonymous Tu non uccidere (Thou Shalt Not Kill), which confronted the question of war, appeared in 1955. Here, Mazzolari resumed work on one of his unpublished texts from 1941, Risposta a un aviatore (Response to an Aviator), which posed the problem of the lawfulness of war. Indeed, don Primo came to accept conscientious objection and harshly condemned all wars. (“War is not only a calamity, it is a sin.” “War does not hold up to Christianity and logic.”)Apart from his books, don Primo spent his remaining energy confronting new themes and familiarizing himself with social problems in other regions. In 1951 he visited the Po Delta, in 1952 he took a trip to Sicily that had a strong impact on him, and in 1953 he went to Sardinia.

In the Italian Church, the name Mazzolari continued to spark divisions; many friends, admirers, and disciples of all types, who identified with his struggles and spread his ideas throughout Italy, opposed the way he was, in practice, prohibited from assuming official positions and confined to Bozzolo. Yet, he remained consistent in his intent to “obey on his feet,” that is, to submit to his superiors while retaining his dignity and his true sentiments.

At the end of his life, some significant signs indicated that the situation was getting better. In November 1957 the archbishop of Milan, Montini (the future pope Paul VI) called upon him to preach at the Mission of Milan, a well-known and extraordinary initiative of preaching and pastoral intervention. Finally, in February 1959 the new pope, John XXIII, received him in the Vatican—an intensely emotional event for don Primo.

By this time, however, the health of don Mazzolari was in decline. In fact, he died soon after on April 12, 1959. Years later, Paolo VI said of him, “He took a difficult path and it was hard to keep after him. As a result, he suffered and we suffered. That is the destiny of prophets.”

History of the Foundation

In April 1959, soon after Primo Mazzolari’s death, a committee was established in Bozzolo to honor him and keep his memory alive by initiating a celebratory commemoration that would take place every year thereafter. At that time, there were already plans to republish don Primo’s out-of-print works and to promote editions of those that had not yet been published. The Mayor of Bozzolo presided over the committee and the secretary, Libero Dall’Asta, maintained contacts with don Primo’s friends and the students who were preparing to write their theses on don Mazzolari.

In 1967, the same year that the first issue of Notiziario mazzolariano appeared, some of don Primo’s sermons, recorded by a parishoner were released in records and later became available in audiotape. Then, in 1970 an anastatic version of the entire Adesso collection was completed.Particular effort was carried out for the ceremony when don Mazzolari’s body was transferred to the Church of San Pietro (April 13, 1969, the tenth anniversary of his death).

In 1981, the don Primo Mazzolari Foundation was formally established and the board of directors nominated don Piero Piazza as President. A Scientific Committee, chaired by Arturo Chiodi, was also established. The foundation was acknowledged legally in 1985 and in 1987 it set up its headquarters in via Castello 15 in Bozzolo.During these years, the foundation frequently held conferences on don Mazzolari and the proceedings were eventually published. The conferences received a significant amount of recognition and the aknowledgment of such figures as Paul VI and John Paul II, as well as the President of the Italian Republic, Francesco Cossiga (1985).

In 1992 the Notiziario became a magazine in its own right under a new header, Impegno. Rassenga di Religione, Attualità e Cultura, which was published bi-annualy.With the death of don Piazza in 1992, don Giusepe Giussani was nominated as the new president of the foundation.

In 1996 an archive was established with as many as 16,000 items, all of which were inventoried.

In 1997 Giorgio Campanini succeeded Arturo Chiodi as president of the foundation’s Scientific Committee. Giorgio Vecchio assumed the position in 2002.